Lyme Disease

Lyme Disease

Tick Basics

Tick Basics

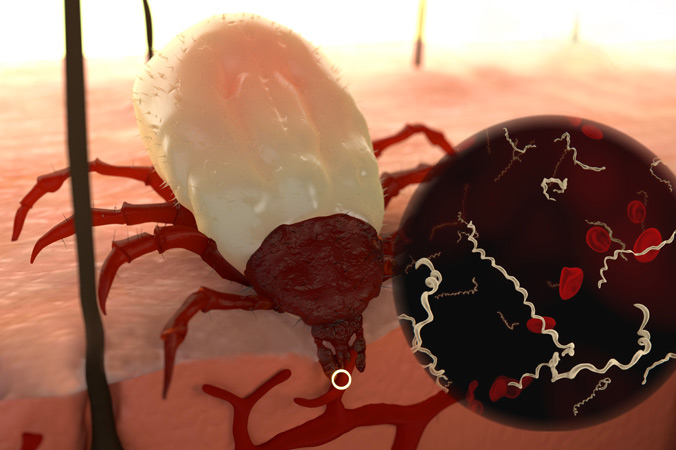

Ticks are tiny parasites that feed on the blood of their hosts (humans and animals) in order to survive and advance to the next life cycle stage. Most ticks have four stages: egg, larva, nymph and adult. The larva and nymph need a blood meal to move to the next stage. Ticks are extremely small, with the nymph the size of a pinhead. The female adult is much larger, and can grow to the size of a sesame seed.

Ticks carry multiple pathogens

Not all ticks are alike, different species live in different regions of the country and can carry and transmit species-specific diseases. With one bite, ticks can infect a human with multiple pathogens, including the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. A single tick can carry over 40 other pathogens. 1 In the Westchester County, NY area, at least 25% of nymphs and 50% of female adult ticks are infected with the Lyme disease bacterium. 2

Tick-borne infections: a threat to humans

Tick-borne infections that pose a threat to humans include Lyme disease, Ehrlichia, Babesia, Anaplasmosis, Bartonella, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Borrelia lonestari, along with several other diseases that have recently surfaced.

Deer, birds and small rodents, like mice and chipmunks, are popular reservoirs for ticks. Family pets can also carry ticks into the home and if loose on the animal’s fur, the tick can attach to an individual and become a potential threat.

Where are ticks most commonly found?

Ticks typically live in tall grass, dense brush and wooded areas, and prefer shaded or moist spaces, like leaf piles. They can remain active in temperatures at or above freezing. In colder temperatures, ticks produce a sort of “antifreeze” that enables them to live through the winter months but they are not active.

Ticks do not fly, jump or fall from trees. Instead, they wait patiently for a host to pass by. Armed with sensors that detect carbon dioxide to identify mammals, ticks use their outstretched front legs to latch onto a host.

Tick Removal

- Using tweezers (preferably with a pointed tip), grasp the tick close to the skin at a right angle.

- Pull upward with even pressure. Do not twist or pull quickly, since this can cause the mouthpart to break off and remain in the skin. (If this occurs, try to remove the mouthpart with tweezers. If unable to, leave it alone and allow the skin to heal. Without the body intact, the tick cannot transmit diseases.)

- Clean the area with rubbing alcohol, and wash hands thoroughly.

Do Not: Use a match to burn the tick off, or substances including petroleum jelly, or nail polish. These methods are not effective with removal.

(You may wish to save the tick by placing it in a ziplock bag in the freezer. Should you become ill and develop symptoms, the tick can be tested for diseases.)

Tick Bites

How Long Does A Tick Need To be Attached?

There’s been debate over how long a tick needs to be attached in order to transmit infectious bacteria. The CDC had been stating, “In most cases, the tick must be attached for 36 – 48 hours or more before the Lyme disease bacterium can be transmitted.” The CDC revised its statement saying, “Blacklegged ticks need to be attached for at least 24 hours before they can transmit Lyme disease.” One study found, the infection could be transmitted within 6 hours of a bite if the tick had been allowed to partially feed on an infected mouse.3

The risk of becoming infected increases the longer the tick is attached and feeding. However, physicians treating Lyme disease patients have found that diseases can be transmitted in less than 24 hours of a tick attachment. 4 Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb) has also been discovered in the salivary glands and ducts of ticks, which could explain a more rapid salivary transmission.5-10

Fewer Than 40% Patients Recall A Tick Bite

Physicians should not rely on the presence of a tick attachment to consider Lyme or other tick-borne diseases in making a diagnosis. Studies have found that fewer than 40% of Lyme disease patients ever recall a tick bite. 11 A leading pediatric Lyme disease specialist, who has treated more than 15,000 children worldwide, has found that only 7% of his patients ever recall a tick attachment.

Often times, tick bites will be confused with spider bites. A tick bite can lead to chronic illness whereas a spider bite does not. Ticks can attach to any part of the body, but prefer areas where the skin is thin, such as behind the knees, belly button, groin, around the ears, and hairline. In small children, it is important to check their scalp carefully, since they’re closer to the ground.

More About Lyme Disease

Learn More

Learn More