Gastrointestinal Dysregulation in Lyme Disease

If your digestion has slowed and nothing seems to help, you’re not alone.

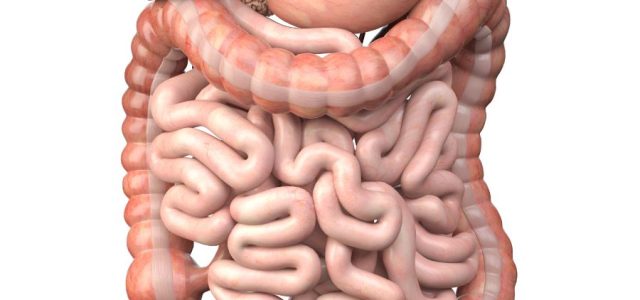

Many patients with Lyme disease develop gastrointestinal symptoms that persist despite dietary changes, fiber supplementation, hydration, or normal testing. These symptoms may include constipation, bloating, early satiety, nausea, abdominal discomfort, or a constant sense that digestion is not moving forward properly.

In Lyme disease, gastrointestinal dysregulation most often reflects broader immune dysregulation, rather than primary gastrointestinal disease. This article focuses on gastrointestinal dysregulation in Lyme disease, a term commonly used to describe digestive symptoms that reflect impaired regulation rather than structural gastrointestinal disease.

This article focuses on gastrointestinal manifestations of Lyme disease and should be read in the context of broader immune and autonomic nervous system involvement.

Importantly, these symptoms do not imply permanent bowel damage.

What gastrointestinal dysregulation means

Gastrointestinal dysregulation refers to impaired control of digestion rather than injury to the gastrointestinal tract itself. The intestines may appear normal on imaging and endoscopy, yet function poorly due to disrupted signaling.

Although constipation is common, dysregulation can affect the entire gastrointestinal tract, from stomach emptying to small bowel transit to colonic motility.

This framework does not exclude other gastrointestinal diagnoses, but it explains why symptoms may persist when standard evaluations are unrevealing.

In Lyme disease, this disruption most often reflects nervous system–mediated dysfunction, particularly involving autonomic control of gut movement and coordination.

Why gastrointestinal dysregulation occurs in Lyme disease

Lyme disease can interfere with the nervous system pathways that regulate digestion. Sustained immune activation, neurologic involvement, and prolonged physiologic stress may alter signaling between the brain, spinal cord, and gut.

Over time, this can leave digestive function unstable and state-dependent, worsening during periods of illness, stress, or poor sleep.

The gut is controlled by the autonomic nervous system

Normal digestion depends on rhythmic, coordinated muscle contractions regulated by the autonomic nervous system and the enteric nervous system embedded within the gut wall.

- Parasympathetic signaling promotes digestion and bowel movement

- Sympathetic activation slows motility and suppresses digestive activity

In Lyme disease, autonomic regulation can become impaired. When sympathetic tone dominates or parasympathetic signaling weakens, intestinal movement slows. Stool remains in the bowel longer, water is reabsorbed, and constipation or incomplete evacuation develops.

This explains why gastrointestinal symptoms can persist even when diet and hydration are appropriate.

For a broader discussion of autonomic involvement across systems, see Autonomic Dysfunction in Lyme Disease.

Dysautonomia can directly slow gut motility in Lyme disease

Autonomic dysfunction is increasingly recognized in Lyme disease and post-infectious syndromes. Patients may experience lightheadedness, palpitations, temperature dysregulation, urinary hesitancy, fatigue, and gastrointestinal slowing as part of the same regulatory disturbance.

When the nervous system remains in a chronic fight-or-flight state, digestion is deprioritized. The gut does not receive consistent signals to move forward.

In this context, gastrointestinal symptoms are not a lifestyle failure. They are a physiologic consequence of impaired autonomic signaling.

Common gastrointestinal patterns in Lyme disease

Patients with Lyme-related GI dysregulation may experience constipation or slowed bowel motility, bloating or abdominal pressure, early satiety, nausea without obstruction, or alternating periods of relative normalcy and worsening.

Symptoms often fluctuate rather than follow a fixed pattern, reflecting changes in neurologic and autonomic stability.

In children, gastrointestinal dysregulation may present as abdominal pain, constipation, or school avoidance rather than classic gastrointestinal complaints.

Why symptoms worsen during flares or stress

Many patients notice that gastrointestinal symptoms worsen during Lyme flares, infections, emotional stress, physical overexertion, or periods of poor recovery.

These are the same conditions that intensify autonomic instability. As autonomic balance shifts further away from parasympathetic support, gut motility slows even more. When regulation improves, bowel function often improves as well.

This pattern mirrors the same recovery limitations discussed in Why Patients With Lyme Disease Feel Exhausted Despite Sleeping.

Visceral sensitivity and gut discomfort

In some patients, gastrointestinal dysregulation overlaps with visceral hypersensitivity, in which normal gut sensations are perceived as uncomfortable or painful.

This sensitivity reflects altered nervous system processing rather than tissue injury and may coexist with broader pain amplification.

For more on this mechanism, see Pain Processing and Central Sensitization in Lyme Disease.

Why routine gastrointestinal testing is often normal

Imaging, colonoscopy, and standard laboratory testing are frequently unremarkable in patients with Lyme-related gastrointestinal symptoms.

Normal test results do not mean symptoms are imagined or insignificant. They indicate that the problem lies in regulation and signaling, not structural damage.

Autonomic dysfunction and functional motility disturbances do not appear on routine GI testing, yet they can profoundly affect digestion.

Medications can worsen autonomic-related GI symptoms

Medications commonly used in Lyme disease—pain medications, certain antidepressants, anticholinergic agents, and supplements such as iron—can further suppress gut motility.

When gastrointestinal symptoms worsen after medication changes, this often reflects additive autonomic inhibition rather than a new gastrointestinal condition.

A clinical takeaway

Gastrointestinal dysregulation in Lyme disease is most often a manifestation of impaired autonomic and neurologic regulation.

The nervous system plays a central role in gut motility, coordination, and sensation. When regulation falters, digestive symptoms emerge—even in the absence of structural disease.

Because this process reflects dysregulation rather than structural injury, gastrointestinal function may improve as neurologic stability returns.

“For a broader clinical framework on how Lyme disease becomes chronic, see Preventing Chronic Lyme Disease.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Lyme disease directly cause constipation or GI slowing?

Yes. In some patients, Lyme disease disrupts autonomic nervous system regulation of the gut, leading to slowed motility and constipation.

Why do GI symptoms worsen during Lyme flares?

Flares often intensify autonomic instability, further suppressing parasympathetic support for digestion.

Is this the same as IBS?

While symptoms may resemble IBS, Lyme-related gastrointestinal dysregulation reflects upstream neurologic control failure rather than a primary gut disorder.

Why doesn’t fiber always help?

If gut motility is impaired, fiber may increase bloating without improving stool passage.

Can GI symptoms improve as Lyme stabilizes?

Yes. Many patients experience improvement as autonomic regulation and overall neurologic stability improve.

Links

Archives of Neurology Shamim EA, Shamim SA, Liss SE, Zafar SF, DeVita E. Constipation heralding neuroborreliosis: an atypical tale of two patients. 2005. PubMed.

Clinical Case Reports Hansen BA, et al. Autonomous dysfunction in Lyme neuroborreliosis. 2018. PubMed.

J Neurogastroenterol Motil. Schefte DF, Nordentoft T. Intestinal pseudoobstruction caused by chronic Lyme neuroborreliosis: a case report. 2015 Jul 3;21(3):440–442. Pubmed

Frontiers in Neurology Adler BL, et al. Dysautonomia following Lyme disease: a key component of post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome? 2024. PubMed.

Gastroenterology Bharucha AE, Pemberton JH, Locke GR. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on constipation. 2013. PubMed.

Last reviewed and updated: January 2026