The accuracy of IgM immunoblot testing for Lyme disease has been debated for years, particularly when IgM is positive but IgG remains negative. This question is especially important in children, where early diagnosis can influence long-term outcomes. A study by Lantos and colleagues provides valuable data on how often positive IgM immunoblots truly represent Lyme disease in pediatric patients.

Children represent one of the age groups most frequently affected by Lyme disease in the United States, making accurate interpretation of testing particularly important in pediatric practice.

Interpretation of Lyme disease tests remains one of the most challenging aspects of diagnosis. For a broader discussion of these limitations, see Lyme Disease Test Accuracy.

Questioning the Accuracy of IgM Immunoblot in Children

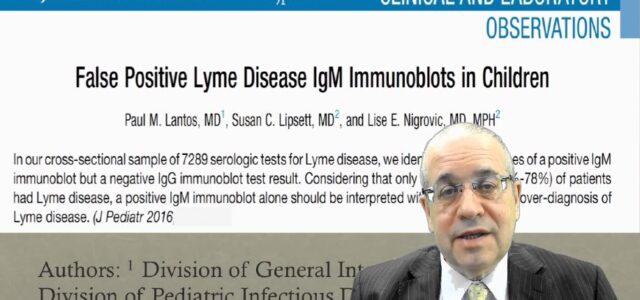

Lantos and colleagues from Duke University Medical Center questioned the accuracy of the IgM immunoblot for Lyme disease in children and adolescents by reviewing a series of patients admitted to Boston Children’s Hospital during a 7-year period.

The study, False Positive Lyme Disease IgM Immunoblots in Children, published in The Journal of Pediatrics, concluded that IgM immunoblots are “valuable in the diagnosis of early LD in children.”

Study Confirms IgM Accuracy in Most Cases

Lantos et al. confirmed the accuracy of IgM immunoblot testing (also referred to as Western blot) in children admitted to Boston Children’s Hospital with suspected early Lyme disease.

Seventy-one percent (119) of the 167 children admitted to Boston Children’s Hospital between January 1, 2007 and June 30, 2014 had Lyme disease. Of these 119 children, “35% (58) had an EM rash and 43% (71) had signs compatible with early-disseminated Lyme disease,” according to Lantos.

“Of the 71 children with signs compatible with early-disseminated LD, 38 had radiculoneuropathy, 28 had meningitis, and 5 had carditis.”

These findings demonstrate that in children presenting with acute symptoms compatible with Lyme disease, positive IgM immunoblot testing is often reliable. The majority of children with positive IgM tests had genuine Lyme disease confirmed by clinical presentation.

Questioning Positive IgM with Negative IgG

Lantos and colleagues questioned the accuracy of the IgM immunoblot for the remaining 48 children admitted to Boston Children’s Hospital because they did not meet established criteria for the disease.

“The 10 children who had signs lasting more than 60 days did not have Lyme disease. The 14 children with arthritis and the 24 with nonspecific signs of 60 days duration did not have Lyme disease,” noted Lantos.

He concluded, “a positive IgM and a negative IgG in a child with a long duration of symptoms, late manifestations or nonspecific clinical presentation is likely a false positive result for Lyme disease.”

This conclusion assumes that all children with symptoms lasting more than 60 days should have developed IgG antibodies. But this assumption overlooks important clinical realities.

Overlooking Genuine Chronic Cases

The analysis may not fully consider the possibility that children with nonspecific signs of Lyme disease lasting 60 days, or who suffer from arthritis and have nonspecific signs lasting longer than 60 days may, in fact, have Lyme disease.

Steere and colleagues described an epidemic in three Connecticut communities of oligoarticular arthritis in children and adults leading to arthritis and nonspecific signs lasting more than 60 days.

“Attacks were usually short (median: 1 week) with much longer intervening periods of complete remission (median: 2.5 months), but some attacks lasted for months. To date, the typical patient has had three recurrences, but 16 [of 51] patients had none,” described Steere, adding, “Over half had concomitant fever (100 – 103°F), malaise and fatigue, headache, and myalgia.”

This landmark description of Lyme disease demonstrated that chronic or intermittent symptoms lasting more than 60 days were part of the original clinical syndrome—not evidence of false positive testing.

Long-Term Consequences in Children

There have been only a handful of studies on children and adolescents with tick-borne diseases, despite the prevalence in this age group and the potential for long-term health consequences.

Bloom and colleagues from Tufts University School of Medicine found, “Five children [of 86] developed behavioral changes, forgetfulness, declining school performance, headache or fatigue and in two cases, a partial complex seizure disorder.”

Vázquez and colleagues from the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation and the Department of Pediatrics reported that children ages 2 to 18 with prior cranial nerve palsy have significantly more behavioral changes (16% vs. 2%), arthralgias and myalgias (21% vs. 5%), and memory problems (8% vs. 1%) an average of 4 years after treatment for Lyme disease.

These findings may also relate to behavioral and cognitive changes described in some children with Lyme disease, discussed further in Behavioral Changes in Children With Lyme Disease.

These findings suggest that dismissing positive IgM tests as “false positives” in children with prolonged symptoms may deny treatment to children who actually have Lyme disease—with potential long-term neuropsychological consequences.

Clinical Judgment in Pediatric Lyme Disease

Lantos and colleagues are to be congratulated for offering additional insight into the importance of a positive IgM immunoblot in children who do not develop a positive IgG immunoblot. This study highlights the importance of using clinical judgment in children who do not develop a positive IgG immunoblot.

The study demonstrates that 71% of children with positive IgM immunoblots had genuine Lyme disease. The question is not whether IgM testing is valuable—the study confirms it is. The question is whether the remaining 29% represent true false positives or whether some of those children have Lyme disease that does not fit rigid diagnostic criteria.

When children present with symptoms compatible with Lyme disease, tick exposure, and positive IgM testing, clinical judgment should guide diagnosis and treatment—not assumptions about what antibody patterns “should” look like.

Video Discussion

I review the study by Lantos and colleagues in an All Things Lyme video blog below.

Frequently Asked Questions

How accurate is IgM immunoblot testing in children?

The Lantos study found that 71% of children with positive IgM immunoblots had confirmed Lyme disease. This demonstrates that IgM testing is highly valuable in pediatric diagnosis, particularly in early disease.

Why do some children have positive IgM but negative IgG?

IgM antibodies appear early in infection. Some children may be tested before IgG antibodies develop. Others may have immune responses that do not follow typical patterns. Dismissing all positive IgM/negative IgG as false positives may miss genuine cases.

Can children have Lyme disease with symptoms lasting more than 60 days?

Yes. Steere’s original description of Lyme disease documented chronic and intermittent symptoms lasting months. Arthritis attacks had a median duration of 1 week but some lasted months, with recurrences occurring over years.

What are long-term consequences of untreated Lyme disease in children?

Studies show children with prior Lyme disease have higher rates of behavioral changes, declining school performance, memory problems, arthralgias, myalgias, and in some cases seizure disorders—even years after treatment.

Should positive IgM with negative IgG be treated?

When clinical presentation and exposure history support Lyme disease diagnosis, treatment should not be withheld based solely on absence of IgG antibodies. Clinical judgment matters more than rigid adherence to antibody patterns.

Clinical Takeaway

The Lantos study provides important validation: 71% of children with positive IgM immunoblots had genuine Lyme disease. This confirms that IgM testing is valuable in pediatric diagnosis, particularly in early disease when IgG antibodies may not yet have developed.

However, the study’s conclusion that positive IgM with negative IgG in children with prolonged symptoms represents false positives deserves scrutiny. Steere’s original description of Lyme disease documented chronic and intermittent arthritis lasting months to years—precisely the presentation that Lantos dismisses as incompatible with genuine infection. The landmark Connecticut epidemic included children with oligoarticular arthritis, recurrent attacks separated by months, and nonspecific symptoms including fever, malaise, fatigue, headache, and myalgia. These are the same presentations Lantos categorizes as false positives when IgG remains negative.

Long-term outcome studies compound the concern. Children with prior Lyme disease show elevated rates of behavioral changes, declining school performance, memory problems, and seizure disorders years after treatment. Dismissing positive IgM tests as false positives in children with prolonged symptoms may deny treatment to those who need it most.

The fundamental question is not whether IgM testing is valuable—the study confirms it is. The question is whether rigid adherence to antibody patterns should override clinical judgment. When children present with symptoms compatible with Lyme disease, tick exposure, and positive IgM testing, clinical diagnosis should guide care—regardless of whether IgG antibodies follow expected patterns.

Related Reading

References

- Lantos PM, Lipsett SC, Nigrovic LE. False Positive Lyme Disease IgM Immunoblots in Children. J Pediatr. 2016.

- Steere AC, Malawista SE, Snydman DR, et al. Lyme arthritis: an epidemic of oligoarticular arthritis in children and adults in three Connecticut communities. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20(1):7-17.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Confirmed Lyme disease cases by age and sex – United States, 2001-2010. Accessed 2016.

- Bloom BJ, Wyckoff PM, Meissner HC, Steere AC. Neurocognitive abnormalities in children after classic manifestations of Lyme disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17(3):189-196.

- Vázquez M, Sparrow SS, Shapiro ED. Long-term neuropsychologic and health outcomes of children with facial nerve palsy attributable to Lyme disease. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):e93-97.